These past few years have been part of a period in which the computing industry, for the first time after many years, has been in flux. The importance of web applications is growing everyday. Alternatives to well-established platforms and application software, often powered by open source software, are challenging the status quo and there was a 5 year period during which there was no new Windows version. While Linux on the Desktop still has a long way to go if it wants to be considered a viable choice for the average, non-technical user, Apple’s Mac OS X is already there.

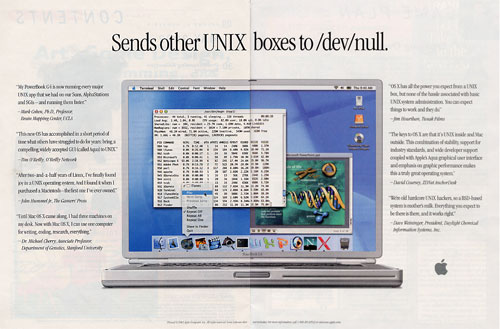

Where does Macintosh and OS X stand in the new Vista (and iPod) world? It is evident that Apple has resigned from its once-prominent We-Love-UNIX-Open-Source-And-Business-Too position of yesteryear. Since 2003 it has gradually redefined itself as a media-centric company, focusing on the iPod, iTS and its professional series of video and photo editing software. Its hardware lines have not been significantly revamped feature-wise, with the exception of the numerous CPU and memory upgrades they have had, since 2004. The target demographics have changed too. Gone are the days when ads like the one above appeared in print (featuring praise from scientists and public figures like Tim O’Reilly), when the Open Source components of OS X were featured in the front page of apple.com, when the XServes were hailed by the IT press as ‘Apple’s bold and impressive foray into the business and scientific server world’ when there was widespread talk of how Apple would revolutionise the UNIX world on the desktop, when Jobs was mentioning how OS X was the most used UNIX operating system in his keynotes. Nope, that’s all behind us now. Mac OS X has its niche, Apple knows this, and is content with that; it is not really focusing on convincing individuals, companies and the world to switch to the Mac, despite the entertaining (to the existing mac user) but ultimately pointless ads.

The differences in usability and æsthetics between OS X and Windows are definitely fewer, after the arrival of Vista, and there might be fewer reasons to ‘upgrade’ to OS X today than there were three or four years ago, but there are countless new reasons for switching to the Mac and many more for which Vista is not an attractive proposition to many users: widespread user fatigue with the ever-present fallacies and shortcomings of Windows, the high price of Vista for consumers (that effectively drives the average PC price up), the privacy/DRM issues involved. All these, as well as the ability of Intel Macs to run Windows natively, make the Mac an attractive option to many and takes the spotlight away from the fact that, on the surface, the next version of OS X, Leopard, seems to be offering very little on top of what Tiger offers today. Low Macintosh prices (compared to similarly spec’ed PCs) are also attracting a lot of people too, people that slowly realise that using ‘Macs are expensive’ as an argument is just not true.

On the other hand, Apple’s line-up may not be to everyone’s taste: the quality assurance problems it’s been facing with practically every single model its released between 2001 to date have been quite serious and numerous (and some have been well documented); it still lacks an ultraportable laptop or a mid-range, extensible, non-integrated desktop computer with powerful graphics capabilities, something like the iMac-Sans-The-Display, or — if you prefer — a Mac Pro Mini. Despite the bold (and very welcome) move to a fully configurable offering for its Mac Pro high-end towers, the rest of its computers are not sufficiently configurable and thus inadequate for many people’s needs; having a high-performance discrete graphics chip on the MacBook as an option is one example of this. Or having the option for higher resolution (and hopefully better quality too) displays on its Professional laptops. Or more options for the graphics cards on iMacs. You get the idea.

The Hackintosh

Ever since the time of Mac OS X DP2, back in 2000, people have been talking about having OS X on PCs. Then there was a period between 2002 and 2004 when you’d regularly find a blog entry or article by a UNIX person on how nice it’d been if a shrinkwrapped OS X version for x86 was released and how quickly people would switch to it and so on and so forth. But of course this never made any sense to anyone knowing Apple, with the Macintosh being its primary source of income and it being a company that had suffered quite a bit from the clone market in the mid 1990s when a significant part of its hardware sales disappeared ‘overnight’ due to cheaper, faster and better clones and at the same time witnessed the fate of NeXT or Be Inc., somewhat similar and related companies that tried to steal market share from Microsoft by risking their existence on the uptake of their competing software before ultimately failing.

Still, since the Intel version of OS X was announced, there has been a lot of buzz on the internet ‘underground’ about the possibility of overriding Apple’s binary protection and running the Intel port of OS X on non-mac, generic x86 hardware. Some went as far so as to suggest that Jobs is gradually preparing the market for a general release of OS X for generic x86 hardware. I do not subscribe to this idea as I have no proof or indication of that (Jobs does not seem to be very interested in increasing the Mac’s market share right now), although I would not rule out that in time, free from the absolute dependency on Mac sales for its survival, Apple might choose to open up the platform, perhaps initially through one or two additional hardware partners (e.g. Sun or HP) to help extend its software platform presence in the server or other markets where it is not active at the moment.

Some months after the first Developer Preview version of Intel OS X came out in mid 2005, the noise became louder and websites, forums and wikis started appearing containing information and sometimes sources or binaries that allegedly made OS X work on non-mac hardware. Today, the community is larger than ever and you can find slipstreamed DVD ISO images with recent versions of OS X for generic x86 Macs on BitTorrent trackers and occasionally patches or drivers can on websites themselves. But do they work? How many people would go out of their way to break the law (at least in many countries) and install OS X on a generic x86 machine, let alone use it for production purposes? How well does OS X run on an average home PC?

There are a lot of people involved with this, judging from the number of messages and activity in some of the largest online forums. Perhaps not that many to irk Apple and merit commercial or legal action, but sufficiently many for Apple to silently update its APSL licence, the once-controversial Open Source licence under which the xnu kernel and the base system upon which OS X is based, to explicitly restrict any use that might help people run copies of OS X in ways Apple does not wish them to.

Since late 2005, tens of people have worked porting drivers from linux to OS X to support previously unsupported hardware, replacing Apple’s encrypted binaries and compiling their own kernel to support older (SSE2) or different (AMD) CPUs. In a sense Apple has benefited considerably from the Open Source parts of OS X: a considerable part of OS X’s security, performance and robustness is not due to Apple’s wonderful engineering, but reuse of proven BSD code refined and tested for many years. Now the fact that much of the core code of its OS is open source is what’s letting people run it on beige boxes. Apple, like many other commercial companies, has had a somewhat flawed relationship with the Open Source community ever since APSL 1.x came out*. This is accentuated by Apple’s new outlook, its perception of the computing industry and its role in it, the importance of the Macintosh and OS X. There is an inherent differenec between the Apple of 1990, that of 2001 and today’s Apple. In retrospect the use of Open Source software in OS X was not exactly something Apple wanted, but rather something Apple had to do. Or was it?

*While APSL 1.0 was approved by the OSI, the Free Software Foundation jumped at Apple for not confirming to its guidelines. In 2003 Apple updated its APSL licence to satisfy the FSFs requirements.

Today, a Hackintosh machine is relatively easy to setup, even with hardware that is not supported by Apple. Contrary to ‘hobby’ OSes there is a huge number of really high quality applications — many of them commercial — that run seamlessly (and very fast) on sub €1,000 machines. Hardware compatibility and stability issues exist, but it’s getting easier for a non-technical person to install and use OS X on their home PC, assuming it’s relatively new. For example, while only SSE3 processors are supported by Apple’s kernel, several custom user-contributed kernels have added support (and optimisations) for SSE2 or AMD processors. Many PC network cards or soundcards are not supported by Apple, but some have been supported through ports of linux and/or BSD drivers to OS X. Until recently, graphics card support was somewhat tricky if you had a card not supported (authorised) by Apple; then a project called Titan (and later its Open Source clone named natit) that sets the registry keys for a number of cards, thus letting them work with Apple’s nVidia and ATi kernel extensions (kexts) was released. There are people that have stated that they are using OS X on non-mac machines as their main OS, although judging by the number of problems, questions and complaints there is a huge gap between the stability and worry-free operation of a Mac and the homebrew version of OS X. For example, besides the bugs and incompatibilities introduced by hastily written, alpha quality drivers and custom kernel patches, updating the system software becomes a chore, especially if a newer kernel or other core parts of the OS become available. Since the ‘cracked’ versions of OS X rely on an ‘unprotected’ kernel, the use of Software Update is not always possible. Failing to install updates might mean security holes, buggy software or a badly maintained system. Installing updates manually would mean spending some time every few months tracking down, downloading and installing custom kernels etc.

Despite it being relatively easy, building and setting up a ‘Hackintosh’ remains a task requiring some technical skills. This is not exactly a task for the faint of heart or those wishing to quickly and painlessly install and use OS X on their old PC and avoid the cost of getting a Macintosh. Still, the fact that people are willing to break the law and spend their time porting drivers, patching and compiling kernels to add support for their non-Mac hardware is token of how appealing OS X is. In InsanelyMac.com, the largest forum on homebrew Macs, I’ve seen posts on how people loved OS X on their hackintoshes so much they eventually sold their PCs and got proper Macs. In some ways, the ‘hackintosh’ can be a trojan horse for Apple, in the same way illegal software was detrimental for Microsoft’s success in many poor regions of the world in the 1990s where whole generations of people grew up with and got accustomed to (pirated versions of) its software. Of course there’s also the opposing view that considers homebrew Macs as bad for Apple’s image, exactly because there is a huge discrepancy between them and a real Mac, both in terms of stability and ease of use (especially setting it up); judging by how technical the hackintosh community is, and how much they go through to get OS X to install and keep running smoothly on their machines, I think this is a non-issue.

And here we are again. Back where we started. The whole experience of setting up a Hackintosh machine really begs the question: Could there be an Apple Supported OS X version for OS X? Would this ever make business sense to Apple? Smoothing the rough edges by providing high quality, Apple or third-party supported drivers for a wider range of peripherals and actively supporting the software, in the same way Intel and PPC Mac OS X versions are maintained today (updates, bugfixes etc.) are the two technical requirements before an official OS X version for generic x86 machines could be realised. That’s something that Apple could very easily do in less than a year. If it did, this would mean that, from a technical point of view, a retail version of Mac OS X along with an official Apple Supported Hardware Compatibility List, would be closer to becoming reality than ever. A new, not exactly open, but distinctive enough ecosystem of Mac hardware would suddenly emerge. Fully configurable, supported by Apple. Whether Apple cares, or would benefit from a product like this right now is arguable. Nevertheless, with the diminished importance of the Macintosh as the sole strategic product (and source of income) one cannot rule out that in the future such a product might be profitable and highly important both for Apple, its developer community and user base.