Thirty years ago my mother bought me a (now vintage) Faber Castell 52/10 ‘Sharpening Machine’. To the 10 year old me this was a very welcome gift, that has adorned all of my desks ever since and helped sharpen hundreds of pencils throughout my life.

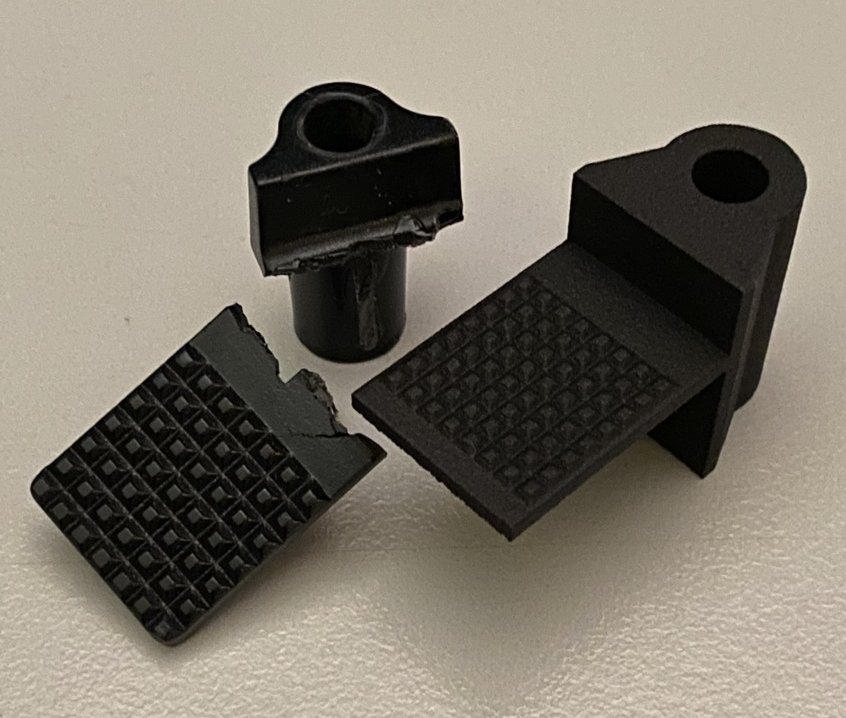

Fast forward to 2020 and my very young son seems to have inherited my inexplicable love for this device, but alas, the combination of the cumulative fatigue on the sharpener clamp and his quite strong little hands resulted in the plastic part that the 52/10 came with — a necessary component for affixing the sharpener to a desk — breaking. This model was designed in the 1970s and originally came with fully metallic parts. By the time my mother bought me mine, the clamp was plastic.

Seeing that I currently have quite a bit of free time, I decided to renew my 3D modelling skills, and at the same time render the sharpener usable once again.

Enter blender, Shapeways and much more money than an old sharpener, even a vintage one like this one, deserves; and a brand new, 3D-printed glass infused plastic clamp that’s more durable and stronger than the original has now materialized and is installed.

I’ve long been intrigued by the potential of 3D printing as a solution to unnecessary waste, cost and obsolescence. Even though designing and ordering my ‘custom’ clamp was certainly not something you’d necessarily do in most cases where sentimental value doesn’t come into play, the economies of scale for 3D printed items are already in place; in fact there are several companies, admittedly limited to niche domains for the time being, that depend, 100% for their production on 3D printed parts. And that’s amazing! And there are also several communities that can already help you find products, and parts, online, such as the Thingiverse.

Planned obsolescence is there, whether we like it or not. And it takes many forms: from components that fail sooner than they have to, to excessive repair costs that render replacement the only sane choice, to lack of spare parts. And, at the same time, there are countless ways companies can make it hard for consumers and third parties to repair and restore their devices. In many cases it’s impossible for anyone to reverse engineer designs. Or, completely untenable for third-parties to keep producing parts for old models of devices, as production runs — using traditional techniques (e.g. injection molding) — require scale in order for them to be financially sustainable/meaningful/profitable. But 3D printing could change all this.

For the Faber Castell clamp I used Shapeways, a 3D-printing-as-a-service company originally founded in the Netherlands and currently headquartered in New York. I’ve been using them since 2012 or so, and they have become somewhat of a staple in the community, due to the great service and insane availability of materials and 3D printers, from SLA, SLS, SLM, to Multi Jet Fusion, Wax Casting and Binder Jetting you can use Shapeways to create pretty much anything that’s 3D printable today. There are other companies like Shapeways that you might want to check out, and several local options, although they’ll probably offer fewer materials.

The cost is obviously high (I built two clamps, one in Nylon and one in Glass bead-infused Nylon) and had to pay about €11 for each clamp plus shipping; which is definitely not cheap. But in many other cases the cost is negligible, compared to the alternatives. And in my case, well, with 3D printing of any part that may break being a possibility, I guess this Faber Castell sharpener machine may be around for my son’s 40th birthday too.