Of all the games that I’ve played over the past twenty five years or so, SimCity, in its various incarnations, has to be the one that I cherish and have spent time playing the most. Ever since I laid my eyes on the first version of SimCity in the early 1990s, I became enamored with it: it possessed this rare and seemingly magical quality you’ll get by reading books — one that you seldom get by playing video games, at least as far as I am concerned: it allows you to engage your imagination, think about aspects of the game that go beyond what the game mechanics, assets and design ever intended. A bit like playing a desktop RPG game, or — even better — Diplomacy, listening to a story or reading a book.

SimCity, released in 1989, was, in many ways, a primitive game even for its time. The graphics were blocky and simplistic, the UI bore considerable similarities to the UNIX Tcl/Tk toolkit, the sounds were minimal (and uninteresting), but the game still became a massive commercial and critical success as it introduced a brand new genre: city (or, more generally, complex-system) simulation. SimCity possessed no explicit storytelling (a major feature of most computer games at the time), apart from the humourous messages (in later versions transformed into scrolling news marquees or newspaper frontpages) that added more style than substance. The reasons behind its success might be numerous and arguable, but chief among them was that it provided an implicit understanding of the dynamics of the city that went far beyond the primitive implementation and the actual game mechanics exposed to the user. As an eleven year old in the early 1990s, oblivious of the actual logic behind the game’s implementation, I ‘enhanced’ the experience of the game in my mind, by creating constraints that were not explicitly there, such as taking into account the distance between utilities or services to city residents, or considering the time it took people to commute between places of work, fun and their home. Many of these assumptions were, of course, wrong, but were eventually added to the game in subsequent versions as features; they didn’t have to be: the magic was already there even when they weren’t.

Somewhere between Two to Three Thousand

I still remember the day I got SimCity 2000, a few years later. The game had tremendously improved, that I literally spent the whole afternoon — and the whole night — playing it, even though I had to wake up early the following morning to go to school. Despite many feature additions and a much improved experience (along with a Macintosh inspired user interface), SimCity 2000 maintained that implicit, open-ended world feeling that made it so fascinating to play; until your city got big enough that is and everyone blasted off from their arcology. This was an attempt, by the Maxis team, to solve the ‘end-game’ issue that had arisen in the original game: it never ended, the challenge dissolved and gameplay became boring as your city grew. Needless to say this was a fantastic game that kept me busy for many hours.

Just before the dawn of the 2000s, SimCity 3000 came out. This was a similarly very welcome update to the now classic series — but an evolutionary one; it may have been that, by that time, my expectations of the realism of the simulation had far exceeded what the game could offer, that I had grown over its limited world and had gradually discovered most of its limited logic that allowed me to ‘win’ in a more or less formulaic manner. The ‘end-game’ issue made a reappareance as Maxis ditched the ‘Arcology’ proposition and reverted to the original’s perpetual lingering metropolis state. While SimCity 3000 was certainly a great game, both in terms of the graphics improvements, the gameplay mechanics, but above all the amazing soundtrack that really set it apart from its predecessors, it wasn’t enough.

Four: The End?

SimCity 4, came out a few months after I started working on my PhD, in early 2003. Like the new version, SimCity 4 was a largely botched release: the game had insane requirements for its time and several bugs that ruined what was actually a pretty good game. It was obviously rushed to the market and it wasn’t until SimCity 4 Deluxe Edition came out several months later that the game came to its own, if you had a powerful enough computer that is. SimCity 4 was a step in the right direction, with much improved graphics, an amazing soundtrack and an ever widening palette of topics, policies and events that made the game fun in the first place. Yet the game was still bound by its micromanagement that made it repetitive and tiresome, especially as the cities became larger. The need to maintain and replace water pumps or demolish old power plants and replace them with newer ones, seemed like tasks that should never have been part of the game, but were there, as gameplay ‘fillers’. There was still no discernible storyline (and no end-game condition either), and the game, while interesting, was quickly predictably growing old on you.

After SimCity 4, it quickly became clear that Maxis, Will Wright’s company — already by that time a wholly owned subsidiary of EA Games — was not really interested in pursuing the SimCity series, at least not in the form it had done so in the past. SimCity was becoming a game for a very specific niche market, while Maxis’s newer franchise, the Sims, was a much more larger success that appealed to a much wider market (I always found it horribly boring and childish). The Sims went on to become one of the most successful video games ever, in terms of the volume of units sold. Will Wright himself said that SimCity was becoming too complex of a game to make financial and commercial sense. He left the game to EA and focused on his next project, Spore which was a very ambitious project that was eventually released to the public in 2008, around two years before he left EA altogether. For a few years no one knew what was going to happen to the SimCity series, until EA announced that they had outsourced the next version of the game to another studio, Tilted Mill Entertainment, and that the game would not be following the same concept or game mechanics as the previous games. Its name was SimCity Societies and it came out in late 2007. It was a critical and commercial failure; the SimCity community found itself stuck with the (by then) aging SimCity 4 and a couple of other games by lesser-known companies that tried to keep the ‘city simulation’ genre alive.

The Road to Five

You can probably imagine I was very excited when the fifth version of SimCity was announced. Now titled simply SimCity, like the original game of 1989, indicating a reboot of the series, the new version was to have a brand-new engine, fully 3D for the first time and a vastly revamped simulation core. Few of the demo videos that came out while the engine was being developed, showed an agent-based, fully simulated society, where resources are created and spent — powering the game’s economy, citizens work, shop and commute and possess a rudiment of intelligence and autonomy. This was the first time the whole game would be dependent, not purely on statistics and probabilities, but on ‘actual’ agents performing actions on their environment. I was very curious to see how this new game would look and feel; how the new engine would allow for a more realistic, but still playable experience.

After several delays SimCity was released in Europe on March 5, 2013. Its launch was a colossal failure, even by EA’s standards, and most certainly one that is going to remembered for years — I don’t recall many other occasions where EA offered disgruntled customers a free game; in my case they also threw in a 15% discount coupon, after using their Live Chat (my game refused to start due to data corruption an issue widely reported on EA’s forum). Of course the launch was a complete failure not because the game is not good (I do cover the actual game below), but because the game – through its always on, always connected to the servers requirement – was literally unplayable by thousands of people that overwhelmed EA’s infrastructure and were left waiting for hours for an available server to allow them to play the game. A number of software bugs were also hurting the game, such as graphics glitches, corrupt user data (that caused the game to crash before it even completed launching and required the deletion of the SimCityUserData folder) and others.

A New Gaming Order

Bugs aside, EA has been spearheading extremely aggressive anti-piracy measures for years. The whole games development industry is undergoing tremendous change. Just last month, the latest and much touted version of one of the most acclaimed racing simulators that ever graced iOS (and Android), Real Racing 3, came out. The company that used to make it, Firemint, were acquired by EA along IronMonkeys – both based in Australia – and where renamed Firemonkeys. The new studio developed Real Racing 3, combined good use of the latest technical capabilities found in Apple’s new iPad and iPhone, i.e. the A6X chip, and their meticulous attention to detail, excellent design and brand and track licensing, resulting in an exceptionally beautiful and very realistic racing game for mobile platforms. A game EA ruined, by employing an aggressive ‘freemium’ model that essentially enforces In-App Purchases as the only way to actually gather enough ‘game currency’ to acquire top-tier vehicles or upgrades. But even a casual gamer will probably have to splurge some cash to buy ‘gold’ or ‘R$s’ if they do not want to wait for their car to be ‘serviced’ or ‘upgraded’.

Playing the Game

Fortunately SimCity does not oblige its users to the demands of such ill-conceived perpetual In-App Purchases like RR3 (you need to part with around eighty euros to get it in the first place), yet its requirements are not much less annoying: the game requires you to be online while you’re playing it; this is not an one-off thing, akin to activation or authentication during startup; this is a permanent requirement of being continuously online while playing. For most people in the western world this may sound ok; they have broadband connections that provide always-on, unmetered connections, at least when they are at home. Does this make the requirement acceptable? I am sure opinions would probably diverge, but when — during launch — it was coupled with EA’s insufficient, underperforming infrastructure that actually prevented thousands of people from playing the game for which they had just paid €80/£50, it becomes a problem no matter where you are (or how fast your connection to the outside world is). The company disabled some leaderboard and achievement features on their servers, rushed to increased capacity, and pledged a free game to everyone that had bought the game during launch. EA did own up to its mega screw up with a slew of ‘blog posts’ by executive and programme managers, including one by Lucy Bradshaw, Maxis’s General Manager, who defended their ‘always-on’ requirement. She invoked their ‘vision’ for the game as the reason for this requirement and claimed it was not a commercial decision. Of course these were extremely weak points, given you can easily create a ‘private’ Region and play on your own and there is nothing in the game that actually requires ‘network’ play. While I agree with their vision and see the value the MMO component brings to the series, I find their excuses weak; and that has nothing to do with their launch screw up either.

After the first few days, many problems continued, as can be evidenced from the company’s forum where tens of thousands of messages describe a bleak experience with crashes, graphics issues, corrupt data, missing cities and so on.

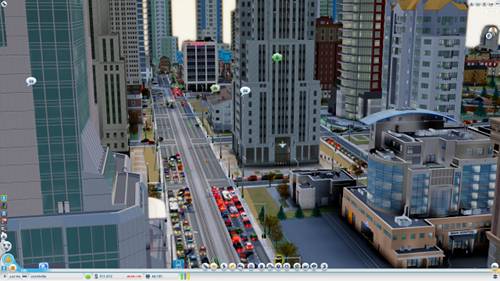

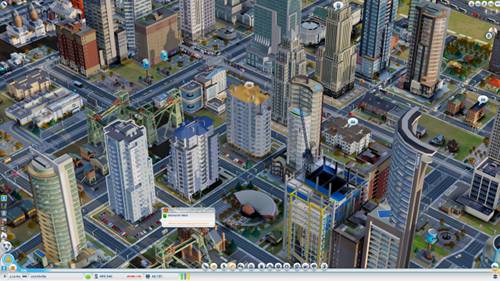

No matter how troublesome SimCity’s launch was however, and it is certainly one of the worst game releases in recent history — it even made the BBC News front page and Amazon quickly stopped taking orders for it — the game itself is by far the most impressive looking SimCity game I’ve played. And that’s not because of amazingly detailed graphics or the beautiful (yet overly monotonous) soundtrack, but for the wholly revamped game mechanics and the open-ended world that the online component offers. This is not your father’s SimCity. The simulation is more realistic than ever, the networked/online component of the game is well-made and ties in well with the concept of the interconnected/interdependent city, but there are some serious flaws to the game that either betray a certain naïveté with regard to what really made SimCity tick in the first place — or, simply, an excessive rush to the market that should never have been there; for example, while the game does away with many of the restrictions of previous SimCity games, like the ‘rigid’ adherence to perpendicular (and 45° in the case of SimCity 4) streets and allows curvy and elliptical streets, the size of the city is fixed (and extremely small), meaning that even with optimal allocation of buildings, roads, rail and green spaces, the city never gets to exceed a couple of hundred thousand citizens — or perhaps slighly more. This seems more like a miscalculation than a conscious design decision to me, as it stifles many of the creative, powerful tools that the player has at his possession and enforces a more ‘conservative’ early 20th century U.S. style city design — exactly what the higher degree of freedom that the new game introduced with roads and variable-sized plots/zoning aimed to do away with! But there is more to this restriction than æsthetics: it makes economics much harder, as resources and ‘industrial deals’ (such as mining ore, smelting metals and building products, or choosing gambling as a financing option) become the primary means for a balanced budget, cities become unable to sustain their services and infrastructure, let alone their growth, by taxes alone.

Many things have changed since the last SimCity came out around 121 months ago. The camera can freely move in 3D, and you can hover at low altitude, just above streetlamps, marveling at the town or small city you just designed. All elements of the game are interactive: you can click on people, vehicles and buildings and find out more about them, or simply follow them. This is the first fully ‘agent-based’ SimCity game, as opposed to a purely statistical/probabilistic simulation, as was the case in the past, and while the concept is extremely appealing, the implementation (and the extremely bad AI) expose the shallow logic behind it. In other changes, the timeframe is now hours and days, as opposed to months and years. Disasters are no longer ‘optional’ features of the game, and can be detrimental to a city’s survival (for example, a nuclear reactor accident will render a considerable part of a city — say 10% — dangerous to the Sims’ health which, coupled with the severely restricted city size more or less ends the game). As I mentioned before, the population numbers in the low to mid hundreds of thousands at best, and not millions, like in previous versions of the game. Plumbing and powerlines follow roads, so gone are the underground pipe laying and power line features. Gone is also the Subway feature, which is now ‘replaced’ by Streetcars — apparently a more suitable option for a small city versus the Metropolis of the past. With all these changes, much of the ‘magic’ of older games is gone, while some of the thrills of the early game is back, as the game is — once again — engaging and challenging. Yet a sloppy implementation means that the joy doesn’t last long.

There is the AI which, at best, is flawed and buggy and that, hopefully, will be improved in the near future as Maxis will patch the game (it has already released several updates); Sims complain of traffic, water, power or sewage infrastructure shortages when there are none, income fluctuates for no good reason within mere hours etc. Vehicles take wrong routes to their destinations. Sims walk pointlessly around the city. There are also many good features missing, like City Ordinances.

Many of those issues are functional bugs that will surely be fixed in future updates to the game (updates automatically download whenever you start the game). What I am most concerned about are the design flaws, the extremely small city size that kills any semblance of creative use of the newly provided tools and features, the removal of some of the most useful inspection ‘tools’ of older games, such as graphing of different metrics of the city over time, the missing transportation options and the over-dependence on city specialization as a budget balancing agent. These issues are much less likely to be fixed and, sadly, mar SimCity. I truly hope Maxis will heed its customers’ advice and feedback and fix them as the rebooted SimCity has the potential to become of the best games I’ve ever played, and arguably one of the best examples of contemporary art — the work of artists, architects and engineers coming together to create an intelligent, informative and entertaining game. I just hope it doesn’t take them ten years to fix it.